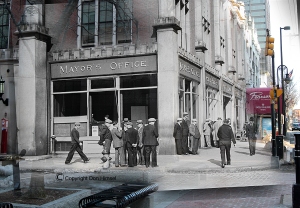

EDITOR’S NOTE: Imagine Nashua: Then & Now is a weekly photo column by Don Himsel. Each week, he will feature an old photo within a more recent photo, along with the story behind it.

Times were tough in the 1930s, and it brought Washington to Manchester.

The Resettlement Administration, Farm Security Administration, and the Office of War Information gave birth to American documentary photography. Photographers working on what was essentially agenda-driven projects traveled around capturing the state of the country, to “introduce America to Americans,” as one writer put it. The project was led by Roy Stryker. The staff list would include people who would become iconic photographers – people such as Dorothea Lange, Walker Evans and Gordon Parks, among others.

The programs and some of the photography that supported them were not without controversy. Bounding over any robust and certainly healthy discussion about propaganda and the like, I’ll refer to Juliet Gorman from her New Deal Narratives website. The FSA photographers, she writes, “through skillful expressive arrangements, could convey the feeling of a common experience.”

Two FSA photographers worked in Manchester in the late 1930s: Carl Mydans and Edwin Locke. The photos can be found through various Internet sources, including university research projects and even Flickr.

Locke worked primarily as Stryker’s assistant, though he did travel, and made some notable photos while in the Queen City. Mydans became a standout photojournalist.

Stryker developed shooting scripts, giving guidance to his photographers as to what to shoot and where to go. Belinda Rathbone wrote in her biography of Walker Evans, “after the Resettlement Administration staff started growing, Stryker gave his less willful photographers as much direction as they could take, including what he called ‘shooting scripts,’ guiding them to make the most of the ordinary.

“‘Bill posters; sign painters – crowd watching a window sign being painted … parade watching, ticker tape; roller skating; spooners-neckers; mowing the front lawn’ went a typical Stryker script …

“‘Waiting for streetcar, newsstand, churches, on Sunday if possible,’ read another copy of notes from Stryker.”

Willful or not, Stryker and his office had regular correspondence with photographers around the country. This passage is from Stryker to Sheldon Dick, who did some work with the FSA. He was headed to Shenandoah, Pennsylvania:

“Shelley … First, the general approach to your problem. Before you touch your camera look the town over carefully. Walk or drive around and around. Look at the people, at the stores, stop at the street corners, and listen in at the filling station and the saloon. Then go back to your hotel and try to write an answer to this question, “why does this town exist?” Only after you have done this will you be able to make up a detailed shooting script. It is terribly important that before you start taking pictures you have in the back of you head a pretty definite feeling as to what makes up the town – is it different from any other town? If so, how and why? As you walk around the town and look at it try to get some feeling of the ‘personality’ of the place. As you make up your shooting script remember that it is an American town and has many things in common with others. I suggest you refer to the general shooting script on American towns before you meet anyone. Try to look at the “skeletons in the closets.” Use your view camera for an overall picture of the place. In doing this you will better prepare yourself to photograph people and how they live.”

How they lived at that time was probably with a heightened sense of anxiety. At the point this photo was made in Manchester, the Amoskeag mills were in deep trouble. The city had developed primarily on its back, and a series of factors were bringing on its demise and subsequent troubles for the people who relied in some way, essentially the whole city, on its well-being.

The list of Manchester photos includes various street scenes, churches, the comings and goings of mill workers, etc. – a fantastic look backwards.

Amoskeag’s situation was no doubt a draw for the government, but New England apparently had its act together enough for it to not figure as prominently in the Feds’ projects until later.

Marsden Hartley wrote in “Race, Region and Nation” that “Stryker felt that New England didn’t fit into the original needs of the FSA, as he considered the region too well ordered and self-reliant.”

Apparently its appearance of capability would come in handy later as war clouds rolled in over the country. It was the “old time rituals” which were becoming important pieces of propaganda: Autumn leaves, roadside fruit stands, etc.

Cliches can make a photographer’s eyes roll. Stryker’s shooting script to photographer Jay Delano, who was headed to New England in 1940, read in part, “I know your damn photographer’s soul writhes, but to hell with it. Do you think I give a damn about a photographer’s soul with Hitler at our doorstep …”

Today, familiar streets fade back to color from the black and white renditions captured years ago. Much has changed. Photos of Marion Street show bright sun on dark tenements that stood where Catholic Medical Center, a credit union and pharmacy stand now. Stores have shut. The canal is gone. Lake Avenue Confectionary over time became the site of the Verizon Wireless Arena.

But through Rathbone’s biography, remaining notes and scripts from Stryker, we can keep in our sights “the kinds of things that a scholar a hundred years from now is going to wonder about.”

Don Himsel can be reached at 594-6590, DHimsel@nashuatelegraph.com or on Twitter @Telegraph_DonH.